By Lance McGinn

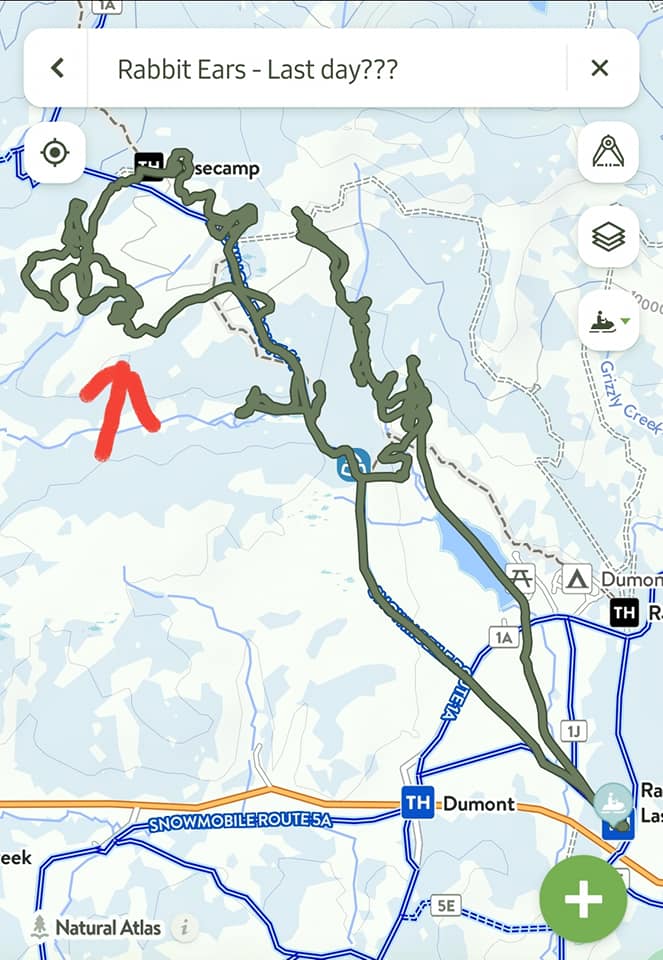

The mountain almost won this weekend. I am happy to be alive! Last Saturday had the makings of a great day for snowmobiling at Rabbit Ears Pass, with 10 inches of fresh the night before on top of 40 inches the week prior. The overcast light that day would make way for another anticipated 24 inch storm that afternoon. Due to this year’s extreme avalanche danger, I’ve resigned to sticking to meadows and mellow slopes. Regardless, the same protocol for preparation takes place: transceiver, radio, avalanche pack, cell phone, chest protector, three sets of goggles and gloves, spare hat, saw, firestarter, solar blanket and bivy sack, first aid kit, hydration, food, full tank gas/oil, spare belt, and tools. The day started off pretty well; after not riding together for five years, Somerset McCarty and I had a chance to open up the 200+ HP Turbo 850s in the fresh. After about three hours of riding, we stopped to take a break. (OK, I got stuck in some sugar but at least we got a chance to rest.)

Soon after, we hit the mellow ridges to claim some more fresh tracks. He went right, I went left and I spent a few minutes hitting the same line over and over to tune my suspension settings. After 15 minutes, I realized that I hadn’t seen Somerset. I killed the engine, listened for his sled, made a radio call, no response. I checked my phone 12:00pm sharp, then I heard a turbo sled over the hill and I went off to chase it down. I found a gulley that led back to the main trail and back to the lot. Once I noticed the sound was not his sled, I began my turn to head back to the last known area. Just over the top of the hill was a large solo tree, which I was going to go around. While navigating in the foggy flat light I was surprised by a set-up three foot wind lip, which I hit. It bucked me off my seat and into a larger wind lip directly behind, which then twisted me and my sled off axis and into a massive five-foot tree well created by a large pine, wind and snow. As I rolled into the well, a ton of snow and my running snowmobile fell on me.

Like most snowmobilers, I have had this happen a time or two and can recover from the situation. This time was different. As I fell, snow surrounded me and packed in my helmet. I was immediately gasping for air and went into panic mode. I attempted to clear the space in front of my helmet only to realize that my hands were packed in pretty tight, with the weight of the snowmobile above. Trying to keep my wits about me, I started breathing through my nose and exhaling downward so as not to create an ice dam, and to buy me some time and clear my helmet. I rolled my wrists and twisted them to my face while using my fingers in my wet gloves to scratch and clear the snow away. After three minutes, I could finally take a deep breath of air — and two-stroke exhaust — while my sled continued to roar on top of me. My next thought was to kill the sled via the tether or kill switch, but as I wiggled my butt outward the 500-pound machine sank another inch, pinning me deeper into the ground and knocking more snow into my breathing area. After clearing the airway again, and breathing a fair amount of carbon monoxide, I stopped all movement to assess the situation. Just then I heard a beep; another two beeps, and the oil-starved engine stopped.

Now I could take the time to breath and think. While I felt OK and had no injuries, the sled had landed on me while I was on my right side. Both elbows were pinned to my chest and my arms were bent at 90 degrees out. The gas tank and seat pinned my head to the ground. I was wearing a chest protector that was firmly pressed by the rear of the gas tank. My right leg was under the rear of the tunnel and my left leg was free to kick past the running board. Carefully, I used my hands to clear as much room as I could in front of my helmet, but I could not clear the moisture or snow from my fogged-over goggles. I was unable to see or remove them. Trying to increase my mobility, I started to move my free leg and clear as much as snow as I could, to see if I could slide out from under my sled. However, the tree well snow was not soft; it was the leftover packed snow that the winds venturi effect had not blown away, and thus created the well. As I pushed my back and avalanche pack into the hardpack snow, I could feel the weight of the sled compressing me even more and pressing the air from my lungs.

I suddenly remembered when I was a kid and my friend Gregory Houlton would wrestle with me. He would put me in some sort of head and leg lock with his weight on top of me. I would start hyperventilating and felt like the constriction would make the veins in my head explode. I couldn’t fathom being restricted in such an awkward position.

I had just become fully aware of the gravity of my situation. Rabbit Ears Pass was expected to get another one to two feet of snow that evening, and I was clearly not getting out without help. I had to focus on staying calm and taking shallow breaths. After 30 minutes, I heard my buddy over the radio: “Lance, Lance this is Somerset. Do you copy?” Over and over I heard an increasingly frantic call for response. Then I heard my cell phone ring out of reach in my pocket. I thought if I could get to my handset on the left breast of my avy pack, I could at least let him know of my situation. At the risk of freezing my fingers, I removed my right glove on my hand to wriggle my hand inward and get a better feel of the pack, and after a couple of unsuccessful attempts I got ahold of the cord of my handset. But the speaker microphone of the handset was on the other side of the gas tank pinning me down. I pressed my leg, attempting to clear some space between the sled and my chest, and over the course of the next five minutes, I attempted to move the sled and pull the cable. With one last effort I gave a strong tug and ripped the wires from the handset that was securely fasted to my pack. Now…radio silence. I sighed deeply and wiggled my fist back into the wet glove and admitted defeat.

As the day grew long and the sky got darker from the blizzard moving in, I could hear engines in the background heading back to the muddy creek lot. In desperation, I yelled and swung my left leg. I had a whistle two inches from my mouth on my pack but it was out of reach from my immobile head. My sounds and movements were muted by the surrounding snow walls. As my throat became increasingly parched, I realized that the ability to shout was a scare resource and should not be wasted on the distant sounds of sleds, indistinguishable from that of numerous aircraft flying in and out of Steamboat overhead.

A lot went through my mind as I lay in that snow well. I ran through all five stages of grief. I recognized that the odds were not looking good, as search and rescue teams generally didn’t jeopardize the safety of others at night and in blizzards. I finally ended up accepting that we all die, and if this was my time and path, then I was OK with this ending. After many thoughts and prayers, when everything was distilled down to the essence, I was remorseful and sorry to my wife and my two tween boys. My boys deserved a father to help them grow to be men of good character. I knew it would be painful for them until our spirits were reunited again. With balled fists freezing, my breath drew shorter. My body was shaking uncontrollably, and I had one last goal — to stay awake. I knew if I fell asleep I was a dead man. If I could stay awake through the night, who knows what could happen. Somerset knew I wanted to be back to the truck by 2:00 pm and could get some riders together. The storm could pass and Routt County Search and Rescue could assemble a search party after the storm cleared in the morning.

Time was a little abstract from there on. I could hear the weather coming in and the snow and wind picking up. Then I heard another snowmobile, louder than any others before. I screamed and waved my leg, as this might be my last chance. The sound grew faint and then strong again. A snowmobile circled the tree and the rider, Ken Russell, noticed an odd sled upside down with about an inch of fresh snow atop. As he circled, it registered that someone might be under the snowmobile. After a second loop he saw a swinging leg and went into hero mode. Ken managed to lift the tail of the sled up about six inches, but I was still pinned in place. A little more maneuvering and I was able to finally break free. I asked if he was a search and rescue member and he said no. He must have been my lucky guardian angel for the day. He swapped me for a set of his warm gloves, dug out the hole so we could right the sled, and broke it free.

It was just after 3:00 pm and I sent a text out to Somerset to let him know I was safe. I had been wedged in the well for over three hours. Barely able to see through the blizzard, Ken guided me back to the lot. After a brief call to my wife, I brought a couple of Coronas over to his trailer. I met his wife Diana and thanked her for letting her husband out to ride solo in this awful weather. Ken is no doubt my hero, and we both knew that if he hadn’t stumbled upon that snow drift on the east side, I wouldn’t have seen my family again. For this I will be forever grateful.

Looking forward, my friends and family have asked if I am going to give up snowmobiling, as this was a pretty traumatizing experience. To be honest, I didn’t know, and for several days afterward I wasn’t even sure if my warm bed was a reality or if my mind was compensating and I was actually still pinned in a tree well, freezing in the backcountry. I asked my wife what I should do and her answer surprised me. She said, “I think you should take a break for a little while, but don’t quit.” Evidently, she knew what she was marrying into.

Going into the backcountry is risky and freak accidents do happen. It was my hero Ken that gave me some sound advice. “No, you can’t give it up. What you can do is learn, so what will you take away from this experience?” As a nearly retired career pilot for United, I could tell that he has that same adrenaline addiction and it doesn’t go away. So here are my takeaways, and of course I am open to others as well:

Communication: Establish ground rules with a partner you have not ridden with for a while or often.

In wide open spaces keep a visual of your partner or group; more than five minutes out of sight, a radio call confirmation is required before proceeding.

Carrying a satellite communicator like a Spot or Garmin inReach Mini (like the one I just bought) could save precious time for others to ping you and locate your whereabouts.

Communicate your trip to other parties with methods of contact and protocols. All other survival preparation methods do not help if you are solo and immobilized or unconscious.

Let neighboring parties know that if you are not back at your vehicle at a certain time, something is wrong, and that your contact information is posted on your vehicle window. I will be laminating something like below and posting on the driver’s window of my truck the days I am out riding:

If you are reading this after dusk, something has gone wrong. Please attempt to contact me. If no response, call 911 for search and rescue.

Activity: Snowmobiling

Date to Return: Saturday 02/20/2021 ETA: 4:00PM

Name: Lance McGinn

Cell # _____________, carrier Verizon, GPS active

Riding with ______________ ,Group Radio: Channel 10 Code: 10Ping

Current GPS location of destination: __________________________

Emergency contact name and phone: _____________

My apologies to Somerset, I can’t imagine the helpless struggle you felt in the radio silence and bearing the weight of being the last contact. Thank you for starting to communicate the situation with other riders in the area.

–Lance McGinn, February 24, 2021